Mild Temperatures are Hindering Zika-transmitting Mosquitoes in the South Central US

by Daphne Thompson, on Aug 23, 2016 10:51:08 AM

Mild temperatures are hindering Zika-transmitting mosquitoes in the South Central US. The unseasonable weather is great news, because the threat unfortunately arrived in the States this year. The presses have been hot lately with Zika articles, particularly about the afflicted location of the Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Many athletes expressed concerns about contracting the virus during their stays, particularly because of what it’s known to do to developing fetuses. Meanwhile, hundreds of US citizens have been infected this summer, not including at least 41 US military members abroad. Zika is expected to spread to every country in the Western Hemisphere but brisk Canada and dry, continental Chile.

What is Zika?

Zika is a flavivirus genetically similar to yellow fever, dengue, West Nile and Japanese encephalitis. Hosts often exhibit no symptoms, but those who do suffer from Zika fever. The primary clinical symptoms are: a maculopapular rash that spreads across the body and often first appears on the face, transient joint pain particularly in the hands and feet, conjunctivitis (pink eye) and a mild fever. Once infected, the virus can be transmitted via blood transfusions or sexually through genital secretions. Typically transmission is male-to-female but female-to-male has also been observed. Unlike AIDS or herpes, it is a virus that goes away over a span of months or years.

There is little knowledge existing regarding the potentially complex side effects of Zika on developing fetuses, but it is well known to stunt development. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Center for Disease Control (CDC) note exacerbated symptoms in pregnant women and their developing unborn, namely many unfortunate cases of microcephaly. Also detected have been other forms of impaired growth, hearing loss, eye defects and Guillain-Barre syndrome, which causes prolonged weakness or paralysis.

Before a sudden outbreak across the Yap Islands in 2007, only 14 cases of Zika were documented - all in Africa and Asia. The recent outbreak, which was revealed by phylogenetic analysis to be distinctly the Asian variety, was first thought by many to have started in Natal, located in northeastern Brazil in August 2014. It was identified as Zika in May 2015 using a reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. Much of the reason for the delay in its identification was that Zika often exhibits mild or no symptoms. This March, the technique of counting virus’ mutations to observe their so-called “molecular clocks” yielded evidence that it first arrived in Brazil the second half of 2013. The timeline corresponds to a now well-researched initial outbreak in French Polynesia in October 2013. The present hypothesis is that it was imported to Brazil inside a traveler and then transferred by a mosquito.

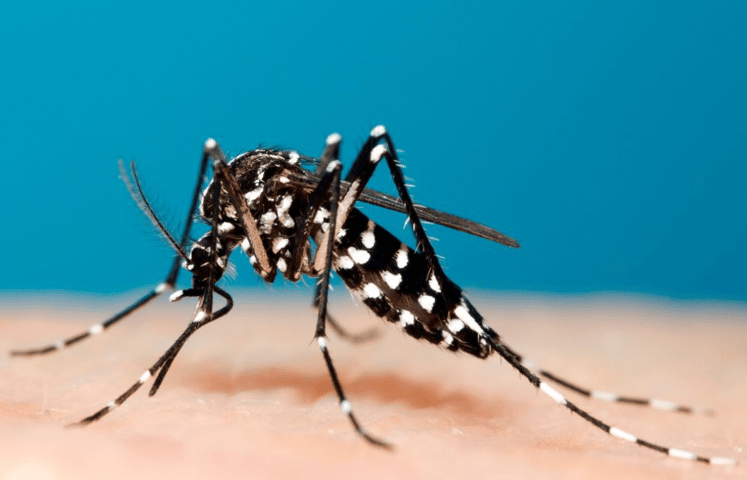

Only two species of mosquitoes are known to transmit Zika: Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. Also known for carrying dengue and chikungunya, Aedes aegypti are active during the day. The original Aedes aegypti were brought to the Americas during the 17th Century on African trading boats. A particularly pestering characteristic of theirs is that they prefer and thrive in urban areas among people.

Aedes albopictus, the Asian tiger mosquito, found its way to Texas in 1985. The species also bites during the day and can threaten areas farther northward, due to their heightened tolerance for colder weather. Albopictus also bites during the day, but prefers the suburbs.

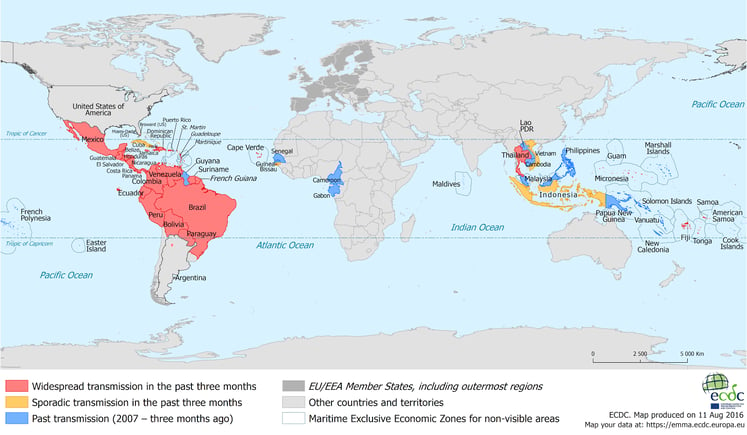

Zika Around the Globe

As of August 2016, Zika has infected around 6,000 people worldwide. Presently affected are Southeast Asia, the Pacific Islands, the Americas and western Africa. Little has been to done to explain why the virus reappeared in French Polynesia sixty-six years after it was discovered, well after the 2007 Yap Islands outbreak. Transmissions in the US began with four cases near Miami, FL. Now at least fifteen have been confirmed there. A dozen of them are within a 150-square-meter area in Wynwood near Buena Vista.

Zika in the South Central US

The threat is now expanding across the US. Consistently hot and steamy weather makes Zika more of a threat in the south. In southern Florida and southern Texas, the virus can live year-round within the two species of mosquitoes. The virus recently made its way to southern and northeastern Kansas. Any area that’s habitable to Aedes aegypti or Aedes albopictus is at risk of Zika either visiting or staying. Many of the infections across the States were imported from another state or country. Transmissions in Texas are said to have rooted from a traveler from Miami. About 1,000 infected foreigners are now living in the US for medical care and research. At 118, Texas presently hosts the most Zika infections in the south central US.

Changes Brought by Recent Weather

The threat has existed in Mexico and the Caribbean for years now, so why did Zika, until recently, avoid the US and why won’t there be a threat of transmissions from mosquitoes in most of the country? Beyond luck, the majority of the reason can be understood by learning about the weather.

Unfavorable changes in environmental factors impact mosquito populations massively. For instance, while mosquitoes need rain and leftover stagnant puddles to breed, forceful or flooding rains can wash out existing laid larvae, hindering the birth rate of the next brood. Forceful winds, perhaps from hurricanes or tropical storms, act to decimate existing populations and their offspring. These threats, however, exist most everywhere mosquitoes can live.

What separates most of the US from the tropics is the southward funneling of cool, Canadian air, which plays a premier role in triggering intense summer storms bringing flooding rains and strong winds. Unseasonably mild temperatures are hindering Zika-transmitting mosquitoes in the South Central US by generally slowing them down. Cooler temperatures force the two host species to go into hibernation. They strongly prefer highs in the 80s, but lately temps have dipped to the 70s near Texas. Higher temperatures are a catalyst for faster basic and reproductive development, but 95°F is roughly the hottest they will tolerate.

Unfavorable environmental factors also limit the extent that the Zika virus can replicate within a mosquito. In order for one to spread Zika from an infected human to another, the virus needs to make its way through its digestive tract, up to its salivary glands. The process, known as extrinsic incubation, normally happens within 10-15 days, but it is faster in moderately hotter temperatures.

The South Central US is witnessing a mild weather pattern, rarely observed in August, helping to alleviate the threat. If the trend continues throughout the end of summer and early fall, mosquito-delivered Zika and West Nile season will end much earlier than usual. However, it is still August and the present reprieve may not foretell how the Aedes aegypti and albopictus seasons will end. To follow the presently diminished but continued threat, follow WDT for regular weather updates.

Track the Threat

Tracking weather that may diminish mosquito populations that either hurt or help Zika transmissions is made easy using several options provided by WDT. Tropical marine travelers, companies operating in threatened areas, Zika prevention-related institutions and anyone planning on being outdoors in a risky area all have an interest in carefully observing the threat. WeatherOps Commander, marine forecasts and tropical reports can help when determining threat levels by clearly displaying temperature predictions and incoming mosquito-decimating storms.